JUDGING THE HIGH ROLLER

by Ted Shih, Denver CO and Terry Rotschafer, Worthington MN

Editors' Note:

High Roller dogs are a joy to watch perform. However, they present challenges for trainers, handlers and judges. Two experienced field trial judges tackle the subject in this Judges' Corner.

Terry: During a conversation with my training group, we discussed judging High Rollers. I commented on how difficult it was for a fast dog to compete in field trials. What do you think?

What Is A High Roller?

Ted: For starters, I think we need to agree upon what is a High Roller. When I hear the words “High Roller”, I envision an intense, powerful, purposeful, fast moving animal. I do not envision, wild creeping, whining animals. I do not envision dogs that run wildly in the field without purpose. My vision of a High Roller is a dog with controlled intensity and power.

Terry: I like your description. I also view a “High Roller” as a dog which has that intense desire to retrieve – on both marks and blinds. I distinguish between a dog with a strong or intense desire to retrieve and a dog which comes to the line and exhibits poor line manners. Bad line manners are simply that – “bad line manners.” I view this as a separate training issue and not part of our discussion.

Why The High Roller Matters

Ted: I think we need to start by asking, “Should we care if High Rollers are at a disadvantage at field trials?” My response is “yes.”

By my count, the Rule Book uses the term “style” eight times. On page 31, the Rule Book tells us that we:

[M]ust judge the dogs for (a) their natural abilities including their memory, intelligence, attention, nose, courage, perseverance and style, and (b) their abilities acquired through training, including steadiness, control, response to direction and delivery. (I have added the emphasis in bold.)

On page 51, the Rule Book discusses style and states:

In all stakes, in respect to “style,” a desired performance includes: (a) an alert and obedient attitude, (b) a fast- determined departure, both on land and into the water, (c) an aggressive search for the “fall,” (d) a prompt pick up, and (e) a reasonably fast return.

I find it significant that the Rule Book uses the words “aggressive” and “fast” in describing positive aspects of style.

As an observer, I enjoy watching a dog with these traits. As a judge, I am told by the Rule Book that these traits are “desired.” So, I conclude that we should try not to penalize the High Roller, and you could make the case that we actually need to “reward” the High Roller.

Terry: In my opinion, we should all be concerned about the overall quality of the animals in our sport. The stylish and fast dog is “pleasing to the eye” and something our field trial rules promote. The dogs that collect the most points throughout a trial season are often the most desired studs and dams of the future. If we penalize High Rollers with tests in which they are at a clear disadvantage, we also reduce their impact on the future gene pool. As an observer, competitor and judge, I find it appealing to watch a dog with intent, purpose and high drive. I like watching the High Roller.

What Practices Penalize The High Roller?

Ted: Let's get to the meat of your inquiry.

Yes, I do think that judges – myself included – penalize the High Roller. In my opinion, this happens most frequently on blinds where there is limited time and space to handle the dog. Some examples of where there is limited time and space in which to handle are:

1. Keyhole blinds.

2. Poison bird blinds.

3. Blinds with tight endings.

4. Blinds in running water.

In each of the above, the handler with the High Roller has: (a) limited time and space to stop and handle the dog through a given hazard; and (b) failure to negotiate the hazard typically results in elimination.

I also believe that tight marks penalize the High Roller.

Terry: I think I know what you are saying, but let me make sure. What do you mean by limited time and/or space?

Ted: By definition, the High Roller is moving more quickly than other dogs. Its handler will have less time in which to react. Moreover, the High Roller will cover more ground after the handler blows his/her whistle before the sound gets there and coming to a stop. The handler with the High Roller has less time and space in which to handle the dog and less margin for error.

Terry: Let’s test this concept out. Let’s take a look at the keyhole blind. To begin with, when you use the term keyhole blind – what do you mean?

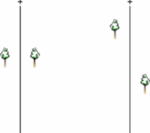

Ted: I distinguish between a “physical” keyhole (see diagram 1) or a “visual” keyhole (diagram 2). I think that the “physical” keyhole unfairly penalizes the High Roller. I don’t think that the “visual” keyhole does.

When the physical keyhole is tight, there will typically be very little room for maneuver. With a High Roller, a handler might only get one whistle and one chance to make the keyhole. With a slower dog, a handler might get two or three casts to make the same keyhole. The handler with the High Roller has limited time/space with which to work. In most field trials, failure to negotiate the keyhole results in elimination. So there is a higher likelihood of the High Roller being dropped.

Terry: Let’s briefly discuss the two types of keyholes you described.

Two trees that are eight yards apart at an equal distance would make a tight “physical” keyhole. Move one of these trees 30 yards deep of the other tree and you have a tight “visual” keyhole from the line, but this type of blind allows the handler of a fast dog the opportunity to navigate their dog through the blind.

Ted: You might also think of a blind that requires a dog to run underneath the arc of a poison bird as a tight physical keyhole.

Terry: You know me too well. In my opinion, two types of poison birds are particularly difficult for a fast dog. They are:

1. A blind under the arc of a poison bird.

2. A poison bird thrown very close to the line to the blind.

Consider this situation. A gunner stands 75 yards from the line and throws a poison bird into a 15 mph wind. The line to the blind is under the arc of the poison bird. How far is the bird thrown? Fifteen yards or less? The window is narrow. There is a tight physical keyhole. Now consider all of the factors present on this poison bird blind:

1. The gunner pops and throws.

2. Your dog watches the bird and the movement of the gunner.

3. The distance from the line to the gun station.

4. Which direction your dog turns.

5. Suction towards, or flare away from, the bird and gun station.

6. Wind.

7. Scent cone of the bird.

8. Possibility that your dog may see the poison bird.

9. Speed of the dog.

10. Stopping distance from whistle to sit.

11. Other factors such as terrain, obstacles or water.

When the High Roller fails this blind, was the failure attributable to:

a) Lack of teamwork between dog and handler?

b) Unwillingness of the dog to take direction from the handler?

c) Or simply insufficient time and space for the good handler with a High Roller to read and react?

If the last is the case, then you must consider the possibility that you as a judge have unfairly penalized the fastest, most stylish dogs, while rewarding the slower more plodding dogs.

All of the above factors combine to make an under the arc poison bird blind extremely difficult. However, the difficulty is increased for the High Roller. There’s simply very little time to (1) read the High Roller’s momentum, and (2) react to the factors. Even the best handlers often fail this blind with the High Roller.

I think that the same penalty occurs when the judges set up a blind where the dogs must come very close to the poison bird – but not under the arc. There is a small window of time and space for the dog and handler. And the High Roller is penalized.

Ted: I think that the other blinds that we mentioned earlier, (a) blinds with tight endings where the dog must be stopped within a very small window of visibility (for example, at the top of a ledge before the dog goes out of sight), and (b) blinds in running water, are also examples of blinds where the person with a High Roller is placed at a disadvantage because there is limited time/space to effectively handle the High Roller. In general, I believe that whenever handlers are presented with limited time and/or space to direct their dogs, the slower, more deliberate animal will hold a significant advantage over the High Roller.

Terry: A problem with each of the blinds we have discussed is that failure to negotiate a very small portion of the blind typically results in elimination. In my opinion, the blind should be judged in its entirety and not based solely on negotiating a keyhole, running underneath the arc of a poison bird, etc. But weekend after weekend, we see dogs dropped for their performance on a few feet of a blind, without any consideration for the rest of their blind.

Ted: I agree that we need to look at the blind as a whole. More importantly, the Rule Book supports your position: “In general, the performance in the test should be considered in its entirety; an occasional failure to take and hold a direction may be considered a minor fault, if offset by several other very good responses.” See page 54.

The blinds that we have described are contrary to the Rule Book’s exhortation to view blinds in their entirety. That is, a dog can have a great initial line, tremendous momentum, carry casts, and yet be eliminated because of its failure in a small portion of the blind. Moreover, this practice often results in the elimination of dogs with great marks.

How Can Judges Not Penalize The High Roller?

Terry: What can judges do to reduce the penalties to the High Roller that we have discussed?

Ted: I think that judges need to recognize the time/space issues presented to a High Roller when designing their blinds.

I try to set my blind parameters so that a good handler with a High Roller can get two whistles at the critical points in the blind. I think doing so allows for a slipped whistle here or there, gives some allowance for poor visibility of either handler or dog, and similarly affords a margin for error where the whistle is hard to hear. If a good handler with a High Roller can get two whistles, then I feel I have given them a fair opportunity to compete. It is virtually impossible to give that to the handler with a High Roller when the blind has a very tight physical keyhole.

I think it is important to recognize that the tight, technical blinds that we so often see in the All-Age Stakes are a reflection of how good the modern dog and handler are and how difficult it is to get results on your blinds – especially the land blinds – without some very tough corridors to navigate. Tight keyholes are popular because they work. However, I think that they are overused, particularly when wind and terrain would provide answers without the need for such drastic measures.

I would urge judges to consider tight visual keyholes – instead of tight physical keyholes. Visual keyholes make it difficult for a handler if the dog does not run straight, but there is still sufficient room for the handler with the fast dog to recover. I think a tight physical keyhole gives a handler only one whistle. A tight visual keyhole might give a handler two or three whistles. I think that the extra whistles are especially important when running the High Roller.

Terry: Another component of a blind often seen is a handler losing sight of a dog immediately before a keyhole. Perhaps the blind angles through a ditch, handlers lose sight of the dog in the ditch, and then the dog suddenly reappears with little space to handle the dog before the keyhole. This is extremely prejudicial to a fast dog. Most All-Age dogs are well trained but you can’t handle a dog you can’t see. Your suggestion that a handler should have time for two whistles is certainly valid in this example.

Ted: The Rule Book says that a blind should be “planned that the dog should be “in-sight” continuously.” See page 42. However, I think that this is unrealistic.

It is the rare tough All-Age Blind, where a dog that is online does not disappear out of sight at some point. I believe that when I have designed a blind where a dog that is on line disappears that if it reappears off line, I should not penalize the dog unless the handler is not able to cast the dog back on line. To put it another way, if a dog disappears out of sight and reappears off line, I give the handler a chance to get the dog back on line. To me it is a way of balancing the Rule Book’s pronouncements with the practical demands of setting a blind in the field.

Terry: Ted, let’s continue with marks which may penalize High Rollers. My starting point would be tight marks. What makes them more difficult and how do they penalize a High Roller? My experience suggests that when marks are short and tight it is difficult for a fast dog. Many times the area of falls may be close, or even overlapping. A fast dog has very little space to hunt before entering another area of fall. By their very nature a fast dog covers more ground and often has a larger hunt area. Handlers are quickly forced to pick up or handle their dog rather than allow the dog a systematic hunt. Dogs that are slower and more methodical have a distinct advantage. They simply don’t cover as much ground and don’t eliminate themselves as quickly. I’m sure you have some thoughts on this subject?

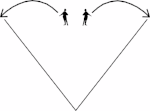

Ted: I think that the problem is in part as you describe. That is, when you have marks that are physically tight (such as a Momma/Poppa, see diagram 3) – as opposed to marks that are visually tight (such as staggered, converging marks, see diagram 4) – the areas of fall (AOF) are very tight, and the High Roller often times runs from one AOF to another. Page 34 of the Rule Book states:

A dog that returns to and systematically hunts the area of a marked fall previously retrieved should be eliminated from the stake, provided, that where the area of the previously retrieved fall overlaps the area of a subsequently retrieved fall, no elimination penalty should be incurred for hunting the area of the overlap.

I think many judges do not permit hunting in the overlap area. Some judges do not allow a dog to run through one fall on the way to another, even if no hunt has been established. As a result, the fast dog is unfairly punished.

Terry: Your diagrams provide an interesting reference. The visually tight set of marks may look tight from the line but they provide two distinct AOFs, clearly separated by considerable distance. These marks allow a fast dog to hunt an area with intent and purpose and not be quickly eliminated by entering an overlapping AOF. This provides a fairer opportunity for all dogs and also helps “level the playing field.” Your reference to the Rule Book illustrates a common problem when trying to judge overlapping AOFs. The overlap is difficult to determine and is inherently quite subjective. Judges are often quick to call a return to an old fall or a switch.

So why not open up the set of marks?

Ted: My preference is always – where terrain and time permit – to have wide open marks. I believe that wide open marks maximize the impact of natural marking ability and reduce the impact of the trained response. The wider the marks – given sufficient terrain and distance – the less likely a skilled handler is able to line the dog to the AOF.

However, I might resort to tight marks, if presented with:

a) Poor terrain;

b) Large entries; and/or

c) Heat issues.

If you are presented with terrain with the contours of billiard table, opening the marks accomplishes little. If you are presented with a large field and are pressed for time, then tight marks that encourage switching (or hunting an old fall) and result in fast pickups may be desirable. Quick, short tests are also needed when heat is a concern.

Overall, however, I believe that many judges use tight marks – regardless of conditions – because they typically provide answers. I think that the tendency of judges to drop dogs that hunt the “overlap” between two tight AOFs is also a reflection of concern about separation and time. Tight marks promote the quick elimination of dogs.

I believe that judges can create many of the same difficulties present with tight “physical” AOFs (e.g., Momma/Poppa) with tight “visual” AOFs (e.g., California double). And that – in my opinion – the former is more likely to penalize the High Roller than the latter.

Returning to our initial topic, I would say that any configuration that does not allow a dog/handler sufficient time and space to react will penalize the High Roller. This is particularly true on blinds.

Terry: I share your opinion of wide open marks. Time, entry size, and the field you are given as a judge play a major role in determining a test. If you are given a field with adequate terrain and a reasonable number of dogs I would prefer open marks and let the natural obstacles of ditches, bushes, clumps of trees, water, slope of ground, etc. determine the outcome. A large number of entries, particularly with short hours of daylight, will force most judges into a compromise. Many trials are run when the weather doesn’t cooperate. Heat may trump everything. Safety of a competing dog should always be our first concern.

What Tests Reward The High Roller?

Ted: Okay, we’ve talked about tests that penalize the fast dogs. What tests reward them?

Terry: Marks that include natural hazards, such as terrain, cover, ditches, etc. (when available) will tend to give all dogs an equal test. The slower dog can get to the fall; however, the High Roller can clearly demonstrate perseverance and style while navigating natural hazards without penalty. I like at least one mark that is difficult to reach. This will often separate the field of dogs and it quickly demonstrates which dogs have that intense desire to find the fall.

When comparing marks to blinds my sense is that competitors are more often frustrated with blinds in which fast dogs are quickly eliminated. Blinds that are fair for all dogs are a function of adequate time to get whistles, preferably two, and adequate space to handle. Given both, High Rollers have been afforded a fair chance.

Ted: My general belief is that the High Roller is more likely than the more methodical dog to punch through difficult terrain. Like you, I believe that the tests that incorporate big terrain, big water, etc., tend to favour the High Roller. I also believe that the High Roller is more likely to go the distance on longer marks. I want to be measured here, though, as I am not a fan of 500 yard marks that some judges favour.

It is telling that I can find more examples of tests that penalize the High Roller than tests that reward High Rollers.

Special Considerations In Evaluating The High Roller

Ted: Are there special considerations in judging the fast dog?

Terry: Our field trial Rule Book (pg. 50) has a long discussion on what constitutes the “area of the fall.” Among the provisions, we are asked to give due consideration for (5) the speed of individual dogs.

My judge’s book contains a provision for “style.” I take many notes when judging and routinely record style for dogs that make an impression on me. Our Rule Book (pg. 50) also states: (7) Dogs may be credited for outstanding style, or they may be penalized for deficiencies in style – the severity of the penalty ranging from a minor demerit to elimination from the stake in extreme cases. I reward stylish dogs when considering callbacks.

Ted: The Rule Book actually instructs us to give the High Roller a larger area of fall for marks than the more methodical dog.

What precisely constitutes the “area of the ‘fall’ ” defies accurate definition; yet, at the outset of every test, each Judge must arbitrarily define its hypothetical boundaries for himself, and for each bird in that test, so that he can judge whether dogs have remained within his own concept of “area of the ‘fall,’ ” as well as how far they have wandered away from “the area” and how much cover they have disturbed unnecessarily. In determining these arbitrary and hypothetical boundaries of the “area of the ‘fall,’ ” due considerations should be given to various factors: (1) the type, the height and the uniformity of the cover, (2) light conditions, (3) direction of the prevailing wind and its intensity, (4) length of the various falls, (5) the speed of individual dogs, (6) whether there is a change in cover (as from stubble to plowed ground, or to ripe alfalfa, or to machine-picked corn, etc.) or whether the “fall” is beyond a hedge, across a road, or over a ditch, etc., and, finally and most important, (7) whether one is establishing the “area of the ‘fall’ ” for a single, or for the first bird a dog goes for, in multiple retrieves, or for the second or the third bird, since each of these should differ from the others.

I have to admit that when I judge, I do not draw a larger area of fall for the High Roller. However, I will write down “fast” if the dog is a High Roller, and in callbacks and placements, will give try to grade the High Roller up. In fact, I once judged a field trial where my co-judge and I had two dogs with very similar work. Style became the tie breaker – and the High Roller won. In retrospect, I wonder if we should have moved the third place dog up a place to make the point that style matters more emphatically.

Conclusions/ Observations

Ted: Terry, as we come to a conclusion, I think that judges need recognize that:

The Rule Book encourages us to reward the High Roller;

Many of the tools that judges carry in their tool box to get answers (tight physical marks, tight physical keyholes, blinds that place a dog close to a hazard from which the dog has difficulty recovering) penalize rather than reward the High Roller;

These tools, while powerful, are not always necessary. In particular, tight visual marks and tight visual keyholes can be very effective and without penalizing the High Rollers as do tight physical marks and tight physical keyholes.

In conclusion, I would ask that the judges in our audience recall that the Rule Book mentions “style” on eight separate occasions and on page 51 states:

In all stakes, in respect to “style,” a desired performance includes: (a) an alert and obedient attitude, (b) a fast determined departure, both on land and into the water, (c) an aggressive search for the “fall,” (d) a prompt pick up, and (e) a reasonably fast return.

If we are to encourage “style” in our dogs, then we as judges need to ensure that our tests are not unreasonably penalizing the High Roller.

Terry: I enjoyed this experience because it forces me to reevaluate my own judging. Most of us that have judged have been forced to use tests that compromise our best judging principles. There are times when the grounds, size of the trial, or weather alter the tests we prefer. Given adequate grounds and time, I would hope all judges consider whether their tests will penalize the High Roller that we all love to watch.

Finally, I would remind readers that our Rule Book states (Pg. 49):

The judges must judge the dogs for (a) their natural abilities, including their memory, intelligence, attention, nose, courage, perseverance and style, and (b) their abilities acquired through training, including steadiness, control, response to direction and delivery.

These few words are immensely powerful!

Comments on Judging the High Roller by Two Professionals

Paul Sletten, Wisconsin

An obvious concern when handling and judging a High Roller is missing a piece of cover because you have time for one whistle and not three. Perhaps people could be judging more on style and the type of dog they want to watch or to breed. Just because a dog has one hunt and some other dog was perfect, doesn’t mean the perfect dog has to win! Perhaps the dog that showed more heart and courage and style is the dog we would rather own, breed to, etc.

Every judge should have an idea of what their perfect dog would look like and then set up tests so those types of dogs do well at their trial. Maybe they like seeing a dog that is strong on a big water test or handles compliantly or does tight marks ... whatever. Each judge’s tests will make a certain style of dog look good. I can’t remember how many times I have had a particular dog win two or more opens under the same judge. That doesn’t happen by accident. That particular dog would excel under the type of tests that judge favoured. Judges need to know if they just like watching High Rollers or if those are the types of dogs they want to win their trial and set up tests accordingly. High Rollers naturally have more inclination to be on the edge of “out of control.” It’s a fine line.

If we talk about “disturbing less cover” while hunting ... perhaps the dog that disturbs a bit more cover but does it in half the time as a slow dog with a smaller hunt is desirable. Doesn’t that give me more time with my dog in the duck blind where it should be with more chance of birds decoying?? Time isn’t a factor at a field trial but perhaps it should be taken into account somewhat???

Dave Rorem, Minnesota

First, let me say – excellent subject matter (long over due), excellent article!

As a trainer, I'm always aware of keeping style, drive, desire and attitude as a significant part of my program while balancing control and trained responses to get a complete package! That being said, over the last 40 years, I'm seeing significant changes in how the majority of judges are setting their tests up so as NOT to give consideration to the High Roller! It has been such a significant change that I have seriously thought about changing some of my program to “tighten down” on the dogs and also my standards on control, so I can survive more of the blinds being thrown at us.

A few things standout: Physical Keyholes that are almost impossible to achieve with a fast dog. Case-in-point: I was running NFC “Willie” in an Open. He had 3 excellent marks in the first series and lined 99% of a land blind and at the very end of the blind they had a super tight physical corridor of 2 small trees. He stumbled as he approached the trees and it caused him to veer right. I stopped him but by the time he heard me and reacted, he was outside the right tree. I cast and he brushed the tree but did not go within the corridor. He was dropped and I asked and they responded that he missed their “mandatory” corridor!

Other places where high rollers get into trouble: Endings of blinds where dog speed is penalized, sharp drop offs, tree lines, blinds in front of steep bank of water, at the gunner’s feet, etc.

As a trainer, all I want from Judges is to follow the rules of our sport. I'm not looking for special treatment for the High Rollers, but I don't want them to be at a disadvantage because of how the tests are set up.

One of the most significant parts of the article that I thought was well said was the descriptive difference between a physical keyhole corridor and a visual keyhole. Very well said and one of the answers needed to improve judging the High Roller!

Diagram 1. Physical Keyhole. Diagram 2. Visual Keyhole.

(combined graphic)

Diagram 3. Momma-Poppa Marks

Diagram 4. Converging Marks

Watch Bill Hillmann's review here

Read about DVD contents here

Order now from Ybs Media here

Read Training Retrievers Alone

DVD Review here

Order from YBS media here

We still have a selection of the valuable Back Issues of Retrievers ONLINE

To find out which issues are still available and costs click here

Currently we have a website launch sale and discounts available.

If you have never seen an issue of Retrievers ONLINE, you can view a complete issue here.

Add A Comment

Comment

Allowed HTML: <b>, <i>, <u>

Comments