A DISCUSSION ABOUT JUDGING THE DERBY

with Judy Rasmuson and Dennis R. Voigt

Authors note: In this article we reference the AKC Derby Stake. However, our discussion is equally relevant to the CKC Junior Stake, with the exception of the flyer. In many ways, it is also relevant to the goals for the Started and Junior in HRC and AKC/CKC Hunt tests. In all cases, we focus on ‘natural abilities’.

From the Standard:

“The judges must judge the dogs for their natural abilities, including their memory, intelligence, attention, nose, courage, perseverance and style, and their abilities acquired through training, including steadiness, control, response to direction and delivery.”

“Natural abilities are of great importance in all stakes, whereas abilities acquired through training are . . . of comparatively minor importance in the Derby stake.”

“… in Derby stakes the ability to ‘mark’ is all-important …”

Dennis: These excerpts from the Rule Book appear straight-forward and are not controversial when you talk to different judges. Yet, if you run a few Derbies it won’t take long to realize that not only are trained abilities required for many Derby tests but that Callbacks often reflect that some judges are putting more than minor importance on trained abilities. Many of us have seen Derby dogs dropped after a couple of “hooked” guns even without a hunt except in the area of the fall. We also see Derby dogs with a couple of hunts or some poor lines to the bird getting dropped. Frankly, I am not sure how much this reflects that some judges have different opinions on what constitutes a good Derby dog or some judges simply set up tests that require considerable trained ability.

Judy: Setting up Derby tests that actually test marking is hard … harder than it used to be, because the Derby dogs have so much more training than in the “old days.” I can’t speak to how other people judge but for myself, I’m reluctant to drop dogs that loop guns or even put on a hunt behind a gun. My goal, in the Derby, is to keep all dogs unless they commit a fatal error – eat a bird, handle, come home without a bird, uncontrolled break, no go, switch, etc. (Editors Note: Please reference the Rule Book section on Serious Faults for “conduct of the dog that in and of itself justifies elimination). However, if the time is short and I can’t get a Derby done by carrying all dogs, then I will drop dogs for persistently hunting out of the area … but hooking a gun or a hunt in the area are not dropable errors in my book.

The location and the size of the hunt are important. Hunts in the area of the fall are not scored down unlike loose hunts and those elsewhere. Particularly, flyer hunts in the flyer field should not be scored down. The flyers are varied and some land in the “ideal spot” and others don’t. A dog that stays in the area of the fall and hunts up the flyer is to be commended. On dead birds, I think of tight area hunts the same as a pin while wide area hunts I think of as looser. At the end of the stake, the size of hunts in the area of the fall might come into play on placements, but it is my goal to have hard enough marks that area hunts are inconsequential.

Dennis: The Rule Book agrees. It has a great section on this topic of pinned marks versus marks with hunts. It says “ability to mark does not necessarily imply pin pointing the fall.” It also says a dog that misses the bird but “quickly and systematically hunts it out” has done well. It further states that such work should not be appreciably out-scored by the pin point. However, it does say that at the end of the day the dog that pins more has an advantage but that is after the entire stake. This is in direct violation of the judge that says “the dog had three hunts so we dropped him.” For Callbacks, what’s important is not whether the dog hunted but where he hunted.

Judy: Generally, when a dog starts a hunt considerably out of the area, the dog ends up being helped or handled … or I hope the test is such that it is hard to recover from a way-out-of-area hunt. If the dog mismarks the bird and hunts behind a gun but eventually comes up with the bird, then I have separation on this test from the dog that hunts the area or pins the bird.

Dennis: I agree with your Derby judging goal of carrying dogs unless there are serious faults. For me, the challenge of a Derby is the difficulty of setting up tests that evaluate marking and not trained abilities. As you said, that is hard these days. There is no doubt that today most Derby dogs that are entered have already received considerable training towards the skills required for advanced all-age work. Thus, many of the Derby dogs display considerable trained abilities. Many of them handle quite well, even though the Rule Book (AKC) does not allow handling for the Derby. Most have had training in de-cheating and they have been coached not to run around water and other obstacles en route to a bird. What judge is not impressed with the dog that goes perfectly straight to a bird and finds it immediately without a hunt? The problem is: where does this leave the Derby dog who also knows exactly where the bird is but doesn’t get there so directly? This is where we see the greatest differences in judging and callbacks.

Judy: If the birds are difficult to find and/or to get to and a dog consistently goes straight to a bird, that performance gives the judges some positive and useful information about the dog. However, if another dog has had “poor” lines but goes straight to the birds too, there is no separation, yet. This puts the onus on the judges to devise tests that actually can separate dogs’ natural abilities and not fall back on trained abilities as the separator.

A corollary to this is to make sure that your tests don’t penalize the trained dog and reward the untrained dog. A go bird that has a long swim which the trained dog makes, while the untrained dog can run the shore easily to make a perfect retrieve, gives the untrained dog the advantage … very little memory drain. Some people will say that they would just penalize the bank runner but that is not a very satisfying solution. Maybe the swimmer has had more advanced training than the bank runner? As a judge you don’t have enough data to make a “lack of courage” call.

Dennis: The diagram in Figure 1 illustrates your point exactly. Dog A swims directly out to and back from the bird which takes 4-5 minutes. Dog B finds his way directly to the bird via land (pinpoints the mark) and does so in 1 minute. Dog B has considerably less memory drain so when sent for the memory bird (which has numerous diverting factors like wind, cover changes, road angles and distance), dog B has a built in advantage that the judges probably didn’t intend.

Judy: The judges were probably thinking about trained derby dogs and were surprised by the cheat. [At that particular trial, the dog that cheated was the only dog that cheated and had the only good job on the memory bird … and, I believe, won that Derby.]

Dennis: This suggests that a major consideration on judging Derby dogs is test design. When I am training I am trying to set up tests that enhance natural abilities but teach trained abilities. But as a judge, I face the dilemma of how to design tests that seek natural abilities much more so than trained abilities. Designing good trial tests is a skill that is a real challenge to acquire, so I go back to the Standard and look at the list of natural abilities as excerpted above for starters. Do you agree and if so, how do you go about this when you are judging?

Judy: Yes, I agree with the Rule Book on the importance of natural abilities and using those abilities as the starter for test design. As a matter of fact, in my judging book, I have those abilities written in bold magic marker on the inside jacket (along with the list of trained abilities).

Also, I have small lists of DOs and DON’Ts that I refer to when talking with my co-judge. These lists help us concentrate on the natural abilities and de-emphasize trained abilities while we set up tests and talk over our judging philosophies.

The following Table 1 is a summary of my DOs.

DOs for the Derby

DO Plan for 8 birds (4 series)

DO keep the flyer separate from other birds

DO call numbers quickly

DO keep gunners and birds visible

DO leave “no man’s land” around marks

DO use terrain instead of technical concepts

DO look for momentum breakers

DO record where the dog hunts

My number one DO is plan for 8 birds. Fewer than this puts too much emphasis on field trial luck. I once ran a derby that had 11 birds – 5 doubles and 1 great derby single. Mac Dubose won it with Gus (NAFC-FC Gusto’s Last Control). Afterwards, he said he’d never finished a derby with that many hunts, much less won! All of us who finished were proud of our dogs and no one thought they deserved better than what they got. No luck was involved by the end of that derby.

Dennis: That is a big one. Too often I have seen Derbies with only 3 tests. Sometimes, one of these tests is a single. Now we are trying to separate 20 dogs on the basis of 5 birds, two of which might be routine go-birds. In some of those cases, the three remaining birds were challenging alright, but primarily because they tested for advanced trained abilities. Eight solid marking birds trumps three training birds in the Derby, hands down.

Personally, I have only gone 5 series once. We had two dogs that could not be separated. One other was very close but behind. That dog got second and one of the top contenders actually dropped to 4th while the other won convincingly.

Judy: DO keep the flyer wide open from other marks. Too tight emphasizes training.

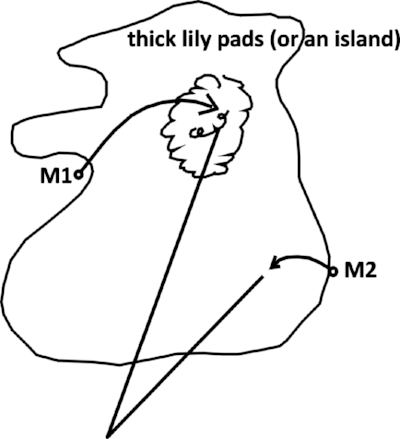

Dennis: I agree but it’s not just about the flyer. In Canada, the Junior stakes have no flyers. Wide open marks can emphasize marks and memory even without the flyer distraction. Nonetheless, we see setups on both sides of the border that emphasize “concept configurations.” Look at Figure 2 where we have a hip-pocket double and a tight-behind the gun double. In the first, the dog is looking at the long gun when trying to check down for the shorter go bird – an advanced trained skill. In the second, it’s often hard to tell even which gunner the dog is looking at. Often the Derby dog doesn’t even see the longer gun and even if he does is likely to head-swing quickly to the shorter gunner. This can take a lot of training to improve. Perhaps the issue is how tight is too tight? Reasonably tight lines are different than extremely close together falls (see my article elsewhere in this issue, “Training Tight” and it will be clear how certain marking skills are strongly related to “trained ability”).

Judy: I’m not against tighter marks in the second land series or the second water series. However, as a judge, I want very clear visual, distance and terrain separation between the guns and between the marks.

Judy: My # 3 is DO call every number quickly. Encourage the dogs to stay focused.

Dennis: I agree, so that when the go-bird hits the ground I call the dog’s number. A long pause often results in a distracted look around or even worse, a break. While steadiness is a requirement, it is also a trained ability, especially when tested to the nth degree.

Judy: Number 4 is very important. DO make guns and marks clearly visible. Check from the dog’s Point of View (POV). They can’t mark what they can’t see.

Dennis: This is so huge, maybe it should be number one! It’s especially important to be sure that the gunners are visible and easily located for the youngsters. Backlighting and other distractions need to be considered more often. The long mark tight behind that was illustrated in Figure 2 requires considerable trained ability for the dogs even to find let alone carefully watch the bird.

Judy: I believe in leaving a “no man’s land” between marks. Leave room for an overrun. Leave plenty of “bad dog room.” Lesser markers often fall into the easy place to go instead of digging out a bird.

Dennis: I was taught and learned early on, “leave room for them to get in trouble and the weaker dogs will!” I always like to leave room behind a gun for a dog. This isn’t always possible but when you tuck a gunner tight up against a bush line, you automatically push a dog toward the bird even if he hasn’t marked it

Judy: Another Do for me is DO concentrate on use of terrain and wind for tests instead of technical concept. In addition, #7; DO look for momentum breakers in placing birds.

Dennis: I assume by this that you mean placing breakpoints such as cover changes or land-water interfaces or terrain changes that cause a decision point or a reason to break down. These are, of course, very ‘grounds’ dependent and need to be carefully sought. They are all the more reason why coming to the assignment with a “concept configuration” in mind is not desirable. Instead study your grounds for best locations.

Judy: #8. In evaluation, I believe it is most important to judge where the dog actually hunts.

Dennis: This is so important and it includes where the dog starts his hunt. This has a lot to do with what we put in our book – a topic we should visit later.

: I also have a short list of DON’Ts

DON’T’s for the Derby

DON’T underestimate influence of scent

DON’T place birds so that dog can wind memory bird while en route to go-bird

DON’T penalize dogs for hooked guns

DON’T set up cheating water marks

DON’T judge lines – judge marking

First is: DON’T overestimate dog’s ability to get past or through scent.

Dennis: As humans our understanding of scent is so poor compared to dogs. They live in a different world that we cannot appreciate. We need to be more aware of our shortcomings and our dog’s strengths. A simple thing is do not scent the area of the fall before the test dog, just in case you have to change the test. But then be sure to scent it well for the early dogs. Secondly, drag-back that develops as more dogs run the test can be an issue. There are a few considerations during test design but the most important thing is to evaluate how drag-back affects the mark. A dog that momentarily “honours his nose” en route to the bird and then continues on to a good mark should not be penalized. In fact, he has probably shown great intelligence and marking ability. A dog that can figure things out and think on his feet is one to watch!

Judy: DON’T place birds so that a memory bird can be winded while a dog is legitimately going to or hunting the go-bird. When this happens, the judges are not able to evaluate marking but have now introduced luck into the equation.

Dennis: Agreed. Even though the Rule Book says that a dog shouldn’t be penalized when it changes route because it smells another bird on the way, we all know that such occurrences often confuse all levels of dogs.

Judy: DON’T penalize dogs for hooked guns. This isn’t useful data. Where the dog hunts is useful data.

Dennis: I smile because how often have we heard from the handler after being asked, “How did you do?” Answer: Okay, but he hooked a gun! The truth be known, the dog hunted probably extensively on the side of the gun opposite the bird. A true hook, wherein the dog simply loops behind a gun and goes directly to the bird, is no different than the dog who is somewhat wide and goes to the bird. Look at Figure 3. What is the difference between dog A and dog B? If your answer is it depends on where he gunner is, I would challenge you to find a Rule Book section to substantiate your view. Yet we see this sort of evaluation many weekends.

Judy: Another Don’t is about cheating water marks. Don’t set up cheating watermarks, like two down the shore and angle entries and re-entries, which require much trained ability. I much prefer to keep the water ”neutral,” that is, the same for the trained and untrained dog.

Dennis: This is a challenge nowadays since so many Derby dogs are trained early on to navigate technical water. I recall a workshop where someone asked Mike Lardy, “When do you think a dog is ready to run the Derby?” He said, “When he can reliably do two down the shore!” I remember thinking my dogs might never be ready and also what a sad state of affairs that we had drifted from trying to find the natural abilities primarily. Unfortunately, Mike was probably describing ‘reality’ these days.

Judy: Related and a major point. “DON’T judge lines.” This isn’t productive to finding the best natural marker. If the marks are hard, the cream will rise through marking and not the route.

Dennis: Well, you saved the Best (or is the Worst?) for last. I fear that many All-Age judges who have been exposed to how much emphasis is placed on lines to blinds and often on marks in today’s All-Age tests can’t ignore lines when they are judging the Derby.

This is further entrenched when new Amateurs train with a Professional. The Pro corrects the young dog for cheating and it is easy to conclude that cheating is poor marking even though the dog knows where the bird is. Correcting the Derby dog for a cheat may be valid in training where we don’t wish to create poor habits that will be needed to be undone later. However, the result is that the distinction between how a dog gets to the mark and whether he knows where the bird is becomes blurred. Our job as Derby judges is not to train dogs but to find the relative best Derby dog based on natural abilities with marking as ‘all-important’. Leave the assessment of the trained abilities like “go-straight” up to the trainer when he goes home.

Judy: Yes, the Book says that marking is ‘all-important’ and the other natural abilities complete the good Derby dog package. Marking, style, attention and memory are relatively self-evident in good Derby tests, but how do you test and judge courage, intelligence, nose and perseverance?

Dennis: Before I comment on that, I want to note that while things like style and attention can be relatively self-evident, I do feel that some judges fail to note either deficiencies in them or indeed remarkable displays. So, when I am judging, I don’t note a normal display of style and attention, but I do note a display of poor style or excellent style. If I see a Derby dog display poor style, I really think that requires recording and quite likely penalizing. But, I agree attributes such as courage, intelligence nose and perseverance can be difficult to assess. I don’t think a lot of judges design their tests to look for these attributes. Not all tests will display them but there are things to consider.

Judy: Yes, sometimes these attributes can be addressed in the test designs. Does a dog want to make a bigger swim after a big swim on the go-bird? Or go back through the ploughed field after having been through it for the go-bird? Does the dog want the memory bird even though he loses sight of the gun for a considerable time? Does the dog want to go into the swamp and dig out the bird? Does the dog want to stay out in the water and hunt the lilies instead of camping out with the gun in the mowed grass? Does the dog want to cross the channel and hunt the island where the bird is? Or bull through the cover to get the bird on the other side? These are legitimate questions to ask of a derby dog without belabouring lines to the bird, assuming that the birds are placed so that the obstacles have to be taken by both a trained or untrained dog in order to make the retrieve.

Dennis: Those are great examples. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate a couple of examples where the dog needs courage or persistence while displaying no aversion to water. These are traits I want to evaluate more so than whether the dog is trained to go straight.

Trained Ability

Dennis: However, let’s go back to the trained abilities. Let’s not ignore these. Certain trained attributes are indeed judged. Our challenge is how to evaluate them and penalize or conversely reward. Let’s not just think about errors but also about that pleasing dog that comes to line perfectly, sits solidly with attention and concentration, retrieves with style while overcoming factors, and delivers cleanly.

Judy: Barking? Creeping? Controlled break? Beating handler to line? Won’t sit? Hard to line up? Doesn’t want to look at any bird but the flyer? Poor delivery? Sticky? Plays with the bird? Lack of a pleasing picture is just that … not pleasing. Though we can love the eager young dog with all of his enthusiasms, the calm, intense, attentive dog will have the day … field work being similar. The Rule Book doesn’t say that trained abilities should be totally ignored, just that they are decidedly lesser.

And as a judge, you hope that those good line manners in the eager dog will translate to better field work. Sometimes it does.

Dennis: And sometimes it doesn’t. This pleasing performance thing as stated in the Rule Book is a Fundamental that perhaps we don’t pay enough attention to as we get more and more wrapped up in our game. I have often said, especially with respect to the Derby, that if you asked 5 naïve people off the street to judge performances they are likely to get it right without any knowledge of the field trial game. They would be attracted to the dog that showed the most style and also got the bird the quickest and most positively. They won’t focus on things like straight line or creeping. While they might not understand the All-Age requirements they might be dead-on for the youngsters.

Judy: So true. My father, who had hunting dogs and had never been to field trials, came to training one day. He didn’t understand the straight line stuff, but he pinpointed the dog that had great style and marks as the dog he wanted to take hunting.

The Rule Book does require delivery to hand. Let’s look at mouth. Poor mouth crops up periodically. Rolling the bird, looking away so handler can’t take the bird, stickiness; such behaviours won’t interfere with the field work, but I do note it and it might figure into placements or RJ; the same with controlled breaks. Creeping, on the other hand, can adversely affect watching birds, particularly if the judge asks for the dog to be re-heeled (which breaks the dog’s concentration!).

Dennis: I agree about controlled breaks. As for creeping, I realize there is an element of training here that may not be refined at this stage. As a trainer, I dislike creeping in the Derby dog. As a judge, I really admire the young dog that is intense, displays high desire and yet remains solid and teamed with his handler. I suspect such a display does not get rewarded enough. However, I have given the Blue to a controlled break Derby dog and would again. That dog went on to be very steady, was a great marker and accumulated many All-Age points.

Evaluating Performance

Judy: Evaluating is all relative. It’s not about perfection but about comparison. That is the tough part. Many times it comes down to apples and oranges … which hunt was better? And which was worse? Was the mannerly, decent marker the better dog or was the yodeling wild Indian who got the birds in a slighter quicker fashion the better dog?

But like all judging, the more information you put on your sheets the better the evaluations will be with your co-judge. Don’t forget to put down line manners and infractions, as well as where the dog hunted. I like to do my drawings real time and not just slap it on the page after the dog has delivered the second bird.

Dennis: I do draw how the dog got the area of the fall but the most important thing I try to record is “where the dog starts to hunt!” That is where the dog first thinks the bird is. That is where he marked the bird. Then I record the hunt because that tells me about the other valuable natural abilities such as nose, perseverance, intelligence and even style. Some judges don’t record the route at all but I think it can tell you about courage and reluctance to enter cover and water and perseverance.

Judy: The line is of little importance to me. It doesn’t confirm anything in my view. If the dog takes a straight line: is that training? Or is it natural? I don’t know. Where the dog hunts tells me everything. This is why particularly in the derby where we don’t have retired guns and rarely more than a double, the bird fall needs to be protected by cover, water, wind, etc. The way to the bird also needs to have obstacles and factors that throw the unsure dog off the bird. But if the dog has major deviations on the way to the bird, and gets the bird clean, then good for the dog. If I was hunting and my dog ran around the water straight to the bird, would I care? No. However, if as a judge I am testing for courage in the water and heavy cover, than the test needs to be set up in a manner that the bird is unretrievable without getting in the water and making the swim or going through yucky cover (this holds for All-Age tests as well as Derbies!). In the Derby, we are testing for NATURAL abilities and not TRAINED abilities.

Further, the Rule Book in its discussion of what constitutes ‘accurate marking’ devotes little time to discussing the line to the bird. Over 90% of the explanation is on the ‘area of the fall’. Then the Book gives 5 lines to ‘disturbing cover unnecessarily’ and ranks that flaw below a quick and obedient handle. The Book does not suggest that the actual line to a mark should be judged.

Having said this, I think that it is easier to set up and judge a derby if judges evaluate lines as well as marks. This gives the less conscientious judges more data points, but I don’t think that the Rule Book supports this kind of judging. In addition, I don’t think the Rule Book supports just judging lines, which often happens when marks are easy to find and hard to get to, i. e. two down the shore. These are the kind of marks that one sets up in training to teach dogs how to go straight. I don’t intend to point fingers as I am guilty of these kinds of marks when I can’t find protected marks on the grounds that I’ve been given. My hope, in that case, is that dogs will get thrown off enough that they will hunt out of the area. But I don’t judge the line. I still judge where the dog hunts.

: No doubt about it that if you judge lines, you have a lot more information that you can use to separate dogs EVEN though the Rule Book will not support you. However, that is not the major reason why I record the route of the dog. The reason is that when I am sitting with my co-judge after a long challenging day, I want to be able to recall the performances of every dog contending for a placement. I really find that the more I have recorded about the dog, the better I can recall. With good notes I am also more tuned into repeated infractions. Some of the other infractions require repeated incidents to be significant – things like reluctance to enter cover or water, loose hunts, noise, unsteadiness and delivery.

Judy: Well, if you are drawing lines to help remember the dog work and not using it to evaluate the relative performance then I’m all for that.

Let’s say something here about noise. Our retrievers are tending to be noisier that they were 20 years ago. Should it be ignored in the Derby? Is Silence the polish that will be acquired before the All-Age stakes? Are all kinds of noise penalized? How much noise is too much? This is something that the two judges need to agree on through reading the Rule Book and discussion.

Dennis: I would definitely agree about discussion with the co-judge and in doing so I would place emphasis on using the Serious/ Moderate/ Minor faults section of the Rule Book.

Wind Saves

Dennis: I would end off this particular discussion with just one of the contentious judging issues that I have encountered. I have been exposed to Judges that declare and debit what they call a “wind save.” An example is a dog running along at full speed, perhaps 40 yards from a bird. The dog suddenly smells the bird and turns and runs directly to it. Some judges assume the dog got the bird primarily because they were “wind saved!” I ask, how do we know the dog wasn’t going to turn in the next stride and start to hunt and to get the bird without a wind save? The way I record and use this result is to view the spot where the dog smelled the bird as the start of his hunt as I described above. Thus if this spot was a few feet away, he started his hunt on top of the bird. If it was 50 yards away it was far less accurate but I do NOT penalize for a wind save!!

Judy: Couldn’t agree more. Wind saves can happen from all different positions but the further the dog is from the bird the less accurate the mark. And then the evaluation is all relative to other dogs and where they started their hunts. I attended a derby once where the judges penalized a dog for winding birds as she came through under the arc. The explanation was that the dog wasn’t marking. She was ‘just winding the bird’. Needless to say, this didn’t feel very satisfactory.

Sometimes, as the stake unfolds, you feel that certain things are unsatisfactory. There is an example of this in the sidebar on the previous page of this article and a solution that worked.

Dennis: Agreed. I’m sure there are other Derby considerations and I am sure there are many other judging dilemmas to be explored. Perhaps, subscribers can suggest them or comment on needs. Regardless, I know there will be a diversity of opinions and thus tests in the Derby and, indeed, in all stakes. That is healthy, but I hope the main “take-home” lesson here is to think carefully about what you are looking for and how you will find it during your next judging assignment.

As always feedback is appreciated.

************************************************************

Side Note 1

Judges Qualifications

The Derby stake often gets the lesser left-over grounds. The Derby often has limited time allocated and may have to wait for dogs because the all-age stakes take priority. Concurrently, the requirements for the pair of Derby judges, both in AKC and CKC, is minimal. Yet, the Derby is an extremely important stake to assess our potential all-age dogs and to develop new judges. It is a very challenging stake to judge, including both test design and evaluation as this discussion suggests. Consequently, we both believe very strongly that at least one of the Derby judges should be a fully qualified all-age judge and one who will mentor the minor judge in many of the finer points of judging such as time management, test design, philosophy of call backs and evaluation of natural versus trained abilities. Putting two “barely qualified” judges together is likely a disservice to them, the dogs and the competitors.

Side Note 2

A Case of Courage and Desire

Based on a judging experience by Judy

Figure 6 shows a 4th series test (A) that was scrapped after a few dogs had run. Why? A terrific young dog got the memory bird without getting wet. My co-judge suggested we just penalize the dog for ‘no courage’. I felt we had no ‘real’ data for that. I suspected that this dog was water shy from the 3rd series even though the dog had pinned every bird in the trial so far. It would not be a good outcome to give the win to this dog if he truly was water shy. We scrapped the test and substituted test B.

The dog in question could not do the test because he couldn’t figure out how to cheat and get the bird. He did not want to make the swim. By putting the line at the water’s edge and the bird at the other side of the water (at the edge) both the trained and untrained dogs were on the same page. This showed us that the water shy dog was too conflicted to get the memory bird.

It also touches on setting up tests that are water neutral. All dogs, trained or untrained, will have the same amount of water to the bird and dogs that want to bail out run the risk of losing their mark.

Watch Bill Hillmann's review here

Read about DVD contents here

Order now from Ybs Media here

Read Training Retrievers Alone

DVD Review here

Order from YBS media here

We still have a selection of the valuable Back Issues of Retrievers ONLINE

To find out which issues are still available and costs click here

Currently we have a website launch sale and discounts available.

If you have never seen an issue of Retrievers ONLINE, you can view a complete issue here.

Add A Comment

Comment

Allowed HTML: <b>, <i>, <u>

Comments