DESIGNING AND EVALUATING BLINDS — PART 1

by Theodore Shih, Denver, Colorado and Dennis R. Voigt

Note: Diagrams for this article are at the end!

Our joint series to date has focused on evaluating marks, first for Derby or Junior dogs at field trials and then on evaluation of marks including flyers at the all-age level. This led us to discussions last issue about designing marks in relation to what we are looking for. While we’ve received some very good feedback, we realize that much variation in interpretation of “relative best” persists. For example, contrary to our view, judging the “trained ability” of the line in Derby and not just the “natural ability” mark near the area of the fall still appears to be a commonplace situation most weekends.

Perhaps one of the most common complaints heard on weekends revolves around the judging of marks versus blinds. The frustration is not just related to how dogs are placed but also to which dogs are called back. We want to tackle that subject, but first, we’ll discuss designing and evaluating blinds by themselves.

Purpose of Blinds and What We Look For

Dennis: The Rule book emphasizes the importance and nature of blinds in various sections.

“A dog which . . . will take direction from his handler is of great value.”

“Judges must judge the dogs for . . . their abilities acquired through training, including . . . control, response to direction . . .”

“A blind retrieve is a test of control.”

At the risk of oversimplifying, I think blinds should be designed to see if the retriever will cooperate with the handler by going where sent and responding to directions in a reasonable fashion. I think blinds should evaluate whether dogs can be directed by their handlers through various hazards, factors and distractions. Those hazards and factors (such as wind, water, terrain and cover) should be things normally encountered in the field – things which cause a dog to get directed away from the bird. As such, distractions such as old falls or poison birds all have to be considered quite legitimate.

Ted: I concur with your general description of the mission statement of a blind. In my mind, a blind is a test of control, performed with style. Because I believe that the blind is a test of control, I will drop a dog – regardless of the quality of its marks – whose handler does not attempt to run my blind.

For example, let’s say that we have a water blind with a very steep and narrow point. The point is clearly on line. A handler who does not attempt to navigate the point – and thereby demonstrate to me the necessary control over his/her dog – is out. That is not to say that the handler who tries to navigate the hazard and fails is back – that would depend upon the work that the rest of the field performed. Rather that a handler who attempted to navigate the hazard would be considered in call backs, while I would simply fold the page of the dog whose handler failed to even attempt to run my blind.

Dennis: I agree that if a hazard is obvious and the handler purposely allows his dog to avoid it, he has failed to run our blind. I have often had problems carrying a dog on the same blind, when the handler attempted to navigate the hazard but failed to do so. This failure is an example of a dog failing to handle. I think the key is, as you say, “it’s not that the handler who tries to navigate the hazard and fails is back, but rather, it means that a handler who attempted to navigate the hazard would be considered in call backs”. At this point the dog’s overall blind and degree of missing the hazard, as well as earlier performance on marks or blinds, is critical.

But, you have raised another very important criterion and that is ‘style’. I agree that the days of ignoring style should be gone. I distinguish between deliberate, slow and cautious dogs with those that act as if they don’t want to be there and don’t want to do the work. The dog that walks on blinds with tail between the legs should never be rewarded with a win. It’s common that such a dog with good marks is called back for another look. Then, perhaps the next blind is just barely acceptable but that lack of style should never be ignored.

Ted: I would go one step farther than you and say that a dog that lacks style should not place. However, the harsh reality is that many judges are fearful of dropping a dog for style, knowing that the handler of the dog they dropped might retaliate by dropping their dog – without cause – when that handler now becomes a judge.

Problems Designing Blinds

Ted: Judging style starts with designing blinds! One of my personal peeves about the keyhole blind is that the keyhole blind favours “piggy” dogs and penalizes high rollers. The Rule Book is rather clear about the need for judges to consider style in evaluating dog work and I think that setting up blinds that penalize style is just plain wrong. When I judge, I try to set up my blinds so that a good handler with a fast dog can get in two whistles at critical portions of the blind. That way, just one cast refusal will not doom a dog to failure if its handler is attentive and fast on the whistle. I think that if a handler with a fast dog only has one whistle, and a handler with a slow dog can get in three whistles, you are putting the high rollers at a serious – and I think – inappropriate disadvantage.

Dennis: That’s a good point and I take note that you said “if its handler is attentive and fast on the whistle”. Fast dogs don’t give you a free pass on poor handling! Those blinds with an extremely critical spot are not uncommon on my circuits either. It certainly absolves the judges of having to judge because so many dogs get picked up. Such blinds can become a case of pass or fail and often the rest of the blind is almost irrelevant. One of the first things that I learned many years ago was to design a challenge near the beginning, the middle and the end of blinds. This way the blind does not get distilled to one critical point.

Ted: Dennis, I agree that the blind should have a beginning, middle and an end.

There are several ways to make sure that your blind has a good beginning:

– Make the entry a hidden one – from a ditch, for example, so that it is difficult to give the dog a good sight picture or destination to seek

– Put an obstacle that the dog either cannot line through – for example, a wall of impenetrable cover, a tree, a gunner – that will cause the dog to deviate and force the handler to adjust

– Angle through a hazard – across a road, a log, a ditch – something that only the best trained dogs will not square

In terms of making your middle work, I think that is where you really need to think about:

– Crosswind (nothing makes a good blind like a nice stiff crosswind)

– Old marks (particularly old flyer falls) that tempt a dog to break down

– Side hills that dogs want to either climb up or fall off

At the end, I like to make the getting to the blind difficult. For example, placing the bird:

– At the base of a hill that the dogs want to flare or climb;

– In a deadfall pocket

– Depressed corner of the road

– Anywhere just sliding by the bird will not get the job done.

I also think that where possible, a natural marker – not an orange stake – should be used to mark the blind. For example, crossed branches, a tree trunk, an unusually shaped rock – something the handlers can recognize, but the dogs cannot.

Dennis: Over the years, I’ve probably implemented most if not all of your tips. These days, I do work harder at trying to not go overboard and fabricating too much. There is no doubt that as judges we get stuck with grounds that make us struggle. You gotta do what you gotta do! I train and handle my own dogs so I’m partial to judging by the “Golden Rule”. Set up and judge like I would like to be judged! Which brings me back to those critical spots and out of sight issues: As a judge, I really don’t get excited when the dog disappears for a minute. This is true en route near the middle of the blind or especially at the very end. I’ve never favoured the blind ending where 2 feet past and the dog is out of side and lost.

Ted: The Rule Book states that a blind “should be so planned that a dog should be ‘in sight’ continuously.” Frankly, I find that it is tough to have a difficult all-age blind where the dogs are not out of sight – albeit briefly – for some period of time. The way I try to account for the fact that a dog may be out of sight – and therefore – beyond a handler’s control is to give a good handler two whistles to get back on line. That is, if a dog is on line, then goes out of sight, and then reappears off line, I try to give the good handler with a fast dog two whistles to get back on line.

Dennis: We agree on this then. When I find that dogs can disappear more quickly than I thought they would at the end of blinds, I don’t judge these brief disappearances with that ‘out of sight out of control’ mentality. I simply don’t favour the pass-fail mentality that some judges seem to practice.

Ted: Almost all of the pass/fail blinds that I see as a competitor involve very narrow corridors with tight keyholes that the dog must pass through to be called back to the next series. I find that the pass/fail keyhole blinds are becoming increasingly popular. I believe that their popularity results from the following:

1) Poorly designed land marks in which most or all of the dogs successfully retrieve the birds, leaving the judges with little or no separation between the dogs. In response, the judges resort to a land blind whose only purpose is to eliminate the dogs and get the field to manageable numbers.

2) A Reluctance – or an inability – to judge a dog’s overall performance. It is much easier for a judge to tell a contestant “you got dropped because you failed to negotiate this specified keyhole” than “overall, I did not find your blind to be ‘pleasing to the eye’,” (Standing Recommendations, Evaluation of Dog Work) when “considered in its entirety” (Standing Recommendations, Abilities Acquired Through Training).

3) An inability to differentiate between a training test – where you are teaching dogs to navigate a very tight corridor and a competition test, where you are evaluating overall performance.

Dennis: I think there are some other blind designs that appear to be targeted to elimination in a pass/fail way. For example, some types of poison birds. It is pretty easy to justify having to get one bird before another in order to demonstrate teamwork on a blind. What is harder to justify is the poison bird that is 5 feet off line at 200 yards.

Ted: I share your disgust (?) at the poison bird set 5 feet off line at 200 yards. I view the test as a variant of the tight keyhole blind I discussed above. In my opinion, it is designed to eliminate dogs and is usually the consequence of first series marks that failed to separate the field.

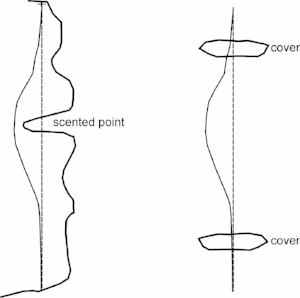

Dennis: I also have a great deal of trouble with the concept of being 5 feet “off” line when there are no hazards or factors or obstacles or distractions. For example, if a portion of a blind has a featureless short cover pasture en route to the blind, what does it matter if the dog is a few feet off line? This scenario is very different than being a few feet off line around a point when the judges have put a scented point on line in order to determine if the “team” can navigate the hazard. In my diagram below one dog has avoided the point but another dog that veers just as much has not avoided any hazard and I wouldn’t penalize much at all.

Ted: I also share your dismay at the blind with “mystery” corridors. I believe that the corridors for a blind should be apparent to the experienced competitor. If they are not, then I think that it falls on the judges to explain their expectations. In this regard, I am puzzled by the sometimes cavalier fashion that some judges employ in placing their mat.

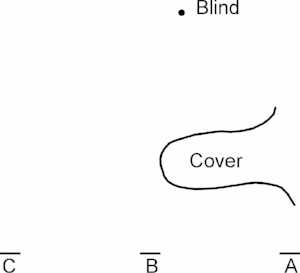

For example, in the following diagram, there is a prominent piece of cover. If the judges want the dogs to negotiate the hazard, then the mat should be placed at Point A. If the judges don’t care whether the dogs negotiate the hazard, then the mat should be placed at Point C. However, you frequently find that the judges place the mat at Point B, which makes their intentions unclear. When I judge, I don’t want any confusion about what my expectations are. So, I would place my mat at Point A or Point C, but never at Point B.

I have heard of judges who place a diagram in the holding blind that illustrates the “ideal” blind. I haven’t done so, but it is something I have considered doing.

Problems Judging Blinds

Dennis: I think the Rule Book gives considerable guidance about what blinds should be like and then how to evaluate them. It says, “On “blind’ retrieves whenever possible the judges should plan their test in such a way that they take advantage of natural hazards, such as islands, points of land, sand bars, ditches, hedges, small bushes, adjacent heavy cover, and rolling terrain.”

That’s a pretty significant list when you read it carefully.

Regarding evaluation of blinds, it says “A blind retrieve is a test of control.” It also says “Response to direction is all important.” Faults or justifications for penalties, include the following: (a) not taking the line originally given by the handler, (b) not continuing on that line for a considerable distance, (c) stopping voluntarily, i.e. “popping-up” and looking back for directions, (d) failure to stop promptly to look to the handler, when signalled, (e) failure to take a new direction, i.e. a new cast, when given, and (f) failure to continue in that new direction for a considerable distance.”

This section goes on to describe how to determine the seriousness of the penalty. Finally, faults are ranked as Minor, Moderate or Serious. All of this provides considerable guidance on how to score blinds. It’s not clear how we got to the place where some judges score blinds as pass/fail, others drop you on a hazard missed by two feet and yet others ignore blinds in choosing the winner? What constitutes a failure, mandating elimination no matter how great the marks?

Ted: Well, the Rule Book lists two serious faults that relate to blinds:

1) Failure to go when sent; and

2) Failure to enter rough cover, water, ice, mud or any other situation involving unpleasant of difficult going ... after being ordered to do so several times, it has failed and must be dropped.

To these two faults I would add a third – failure to attempt to run the blind set by the judges. Other than these three situations, I will give a dog that crushed the marks, a great deal of latitude during call backs.

Dennis: I would add another and it is, “repeated failure to take directions or not stopping on a whistle he should have heard.”

Rule Book excerpt: A dog which pays no attention to many whistles and directions by his handler can be said to be “out-of-control,” and unless in the opinion of the judges there exist valid mitigating circumstances, should be eliminated from the stake. I note it says “many”. I was quite amazed earlier this summer to read results from a poll on an internet retriever training forum which asked about cardinal sins when judging blinds. The discussion centered on “no-goes” on a blind when sent. This failure to go when sent is listed as a major fault as you indicate above. Under the General section, the Book states that “A dog when sent on a blind retrieve should at once proceed in the general direction of the line given by the handler.” Perhaps this explains why some judges penalize a poor initial line so severely.

However, what amazed me in the forum poll was that a significant percentage of respondents answered that they would drop a dog for a slipped whistle, a pop, and a cast refusal. Such faults, while all listed in the excerpt I quoted above, are also all listed under minor faults when committed but once. It’s not clear why we see such severe evaluation on blinds, when it is contrary to the Rule Book.

Overall, I see a great deal of variation in how judges penalize casts. There are a handful that pay attention to what cast is given but I think most are inclined to correctly evaluate what the dog does in relation to getting the bird, not in relation to what cast the handler gave. However, evaluating casts is, perhaps, one of those areas where judges have a tendency to conjure up their own rules that can’t be found in the book. Examples include not progressing towards the blind, handling in on a cast en route to the bird, scoring delayed vocals or 2nd whistles excessively hard as two casts or refusals.

What is a reasonable change in direction or carrying of his casts will always be relative and variable. However, when a dog needs the same line correction 5X in 50 yards, demerits for cooperation are warranted. But how much do you demerit for a single pop or a whistle before the water or an early line correction or a brief disappearance at the last dyke is not so clear. What’s more unclear to me is why some judges consider these eliminating faults.

Ted: I, too, am astonished at how many judges will drop a dog for a single pop when the Rule Book lists a pop on a blind as a minor fault. Those judges have not read the Rule Book or deliberately choose to ignore it. Neither option is acceptable.

I am also surprised at how many judges consider double tapping – that is using a second whistle when a dog is seated to reinforce control – on a blind to be “intimidation” when the Rule Book is clear that intimidation occurs on the line, not in the field.

Perhaps this is a good place for me to discuss another aspect of the judging of blinds that I find perplexing – that is, why judges have lopsided corridors for their blinds.

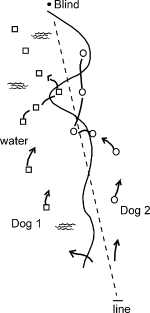

Consider my following diagrams of 2 dogs. Oftentimes, you will see judges call back Dog 1, but not Dog 2, when the dogs have interchangeable work. Why? I think it is because on a very simplistic level, judges believe that a dog seeking water in a water blind is to be preferred over a dog seeking dirt. However, the blind that the judges set requires that the dogs get in the water very close to the shore. Why then should Dog 1 be favoured over Dog 2? ... Because many judges are lopsided to water! It is apparent when you look at the pattern of the dots that the handler was having a hard time persuading his dog to get in the water. Compare the dots to the squares. It is obvious that Dog 2 has run a better blind.

Dennis: I agree with you as I have run blinds that were scored in a lop-sided fashion on both land and water. On land the lop side often favours the close to hazard side as opposed to the shoreline water blind.

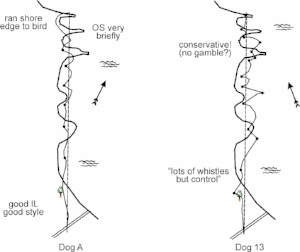

As I looked at your drawings I was reminded that I have seen judges apparently biased by how they drew their diagrams. Like you, I do not write CR for cast refusal. But I do mark the spot with a dot where every whistle is given. I also draw the actual route of the dog because I cannot assume it followed a straight line between dots. In fact, quite the opposite is often true. I also like to add 2 other things, one is the perfect line and the other is the location of key hazards in the blind. As an example, I’ve included a couple of actual examples from my recent National Amateur judging of the 8th series water blind. The bottom line is that you should be able to recall the performance accurately.

Eventually, the tough discussion becomes how you balance performance on marks and blinds.

Ted: I used to say that each mark and blind was a bird and that, over the course of a trial, their relative merits would be scored. But, I have come to conclude that is too simplistic. For example, why should a very tough water blind, with a long entry, into cold water, with a hard wind pushing the dogs into dirt – that very few dogs can do well – be considered to be equal to a mark that for one reason or another, almost all of the dogs retrieved with little difficulty? I think that good judging requires a more flexible approach, where each mark and blind is evaluated on its individual merits.

Dennis: Sounds like a good topic for next issue!

Figure 1. Navigating “Hazards” in Blinds

Figure 2. Mat Placement for a Blind

Figure 3. Judging Blind Work

Figure 4. Drawing Blind Work

Back to Top

Watch Bill Hillmann's review here

Read about DVD contents here

Order now from Ybs Media here

Read Training Retrievers Alone

DVD Review here

Order from YBS media here

We still have a selection of the valuable Back Issues of Retrievers ONLINE

To find out which issues are still available and costs click here

Currently we have a website launch sale and discounts available.

If you have never seen an issue of Retrievers ONLINE, you can view a complete issue here.

Add A Comment

Comment

Allowed HTML: <b>, <i>, <u>

Comments